Another Blog post from bmwcse.com, repeating much of what has already been posted in this thread, but as a whole story:

Battery Box

Unless we plan to drive our car using a very long extension cord, we have to get our battery modules off of their cart and into the car. Our plan is to get the majority of the modules in the engine bay, with a couple more in the trunk. Here’s the story…

Volts, Watts & Cells = Snoozefest, or Skip this Section if you Like

I have written and deleted here several times a fairly detailed explanation of how battery cells work. How you chain them together to increase voltage. How you group some of these chains together to increase their endurance. It was all very fascinating, but it took several pages and I fell asleep just editing it. So feel free to google all about it if you like.

My point in writing about it was to answer the question I often hear: “Why do you need so many batteries in your car?” It’s a terrific question. In fact, one of my favorite classic car EV conversions uses a high voltage Tesla motor like ours, but with Chevy Volt battery modules. Each module is not only smaller than the Tesla modules, they also output twice the voltage. We could get by with 6 smaller modules to properly run our car. That’s 1/3 of the size, weight, and cost of the Tesla modules. That sounds like a perfect solution.

Why then would we choose to go with 12 larger, heavier, more costly Tesla modules? kWh is why. Kilowatts Per Hour is the measurement of how long your module will last when being used. The majority of non-Testa EV battery modules have a very low kWh rating. This is finally beginning to change now that more auto manufacturers are taking EVs seriously, but we are years away from seeing these better modules in the used (salvage) market the way Tesla modules are today.

Teslas are good for 240 miles of range in some of their least capable configurations. Our car will be much lighter than a Tesla, but far less aerodynamic. We are confident that our 72 kWh battery configuration will get us over 200 miles of mixed city and highway driving. And in case you are wondering: no, we won’t be able to plug into a Tesla Supercharger on road trips to extend the range. However, we will be able to plug into the generic charging stations that are popping up everywhere.

Starting with an Open Engine Bay

We now can benefit from all the work we have done to open up that engine bay: The bulky steering box and linkage that we swapped out for our compact and low steering rack; The large brake setup which was swapped out and relocated into the transmission tunnel (thanks to Greg). We have earned ourselves a very wide open area for our new battery box.

A Sheet of Aluminum and a Table Saw

To properly mount and protect the battery modules inside the engine bay we need an enclosed box. To keep the weight down as much as possible, we built our battery box out of aluminum. By using all the space possible, our box will hold 12 Tesla modules. We will need to put 2 more modules into the trunk.

Aluminum cuts smooth and easy on a tablesaw as if it were a piece of thin plywood.

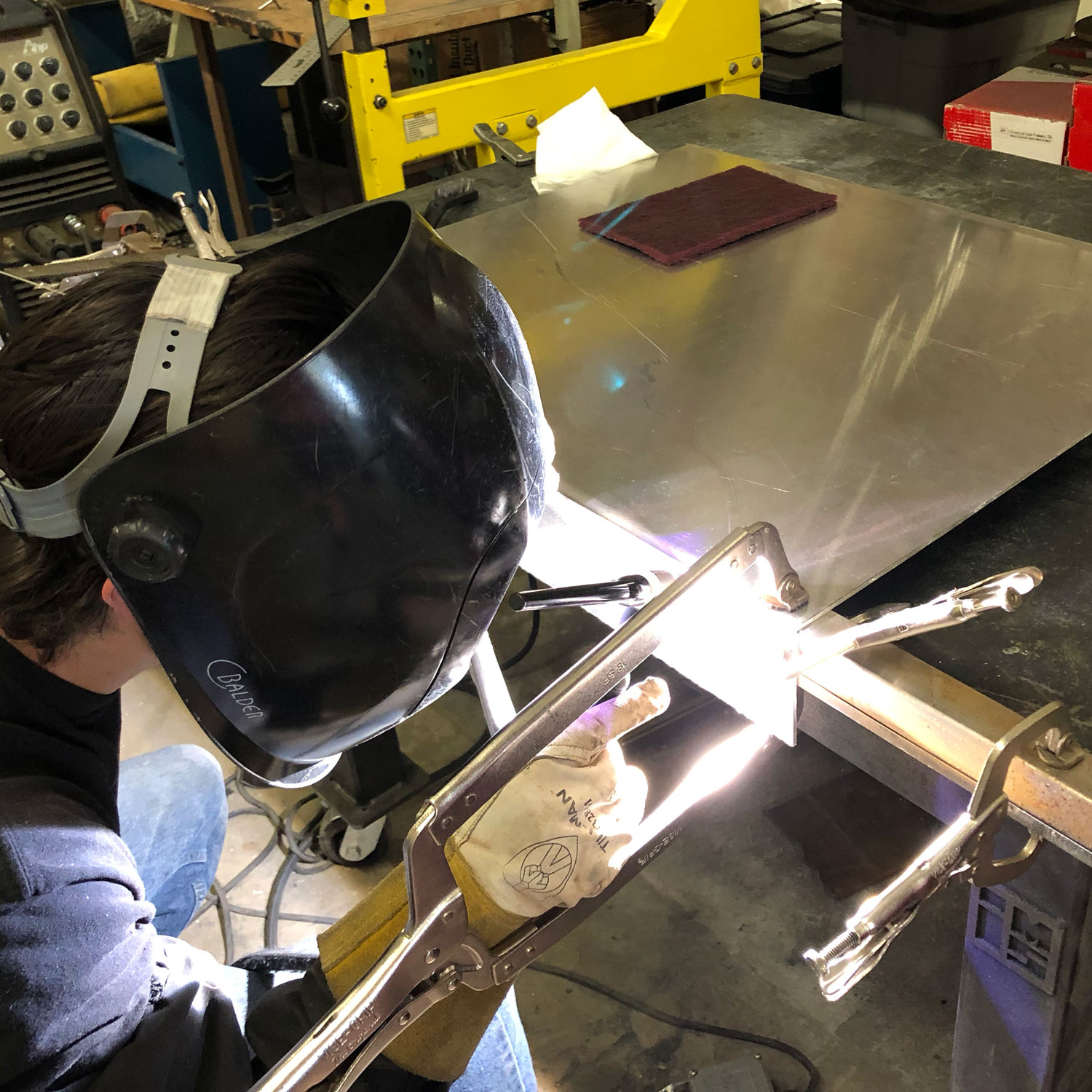

Tyler is a master with the tig welder. I learned a lot about welding aluminum on this project. Very tedious.

In between the car’s frame rails we are able to squeeze in a lower section holding two battery modules.

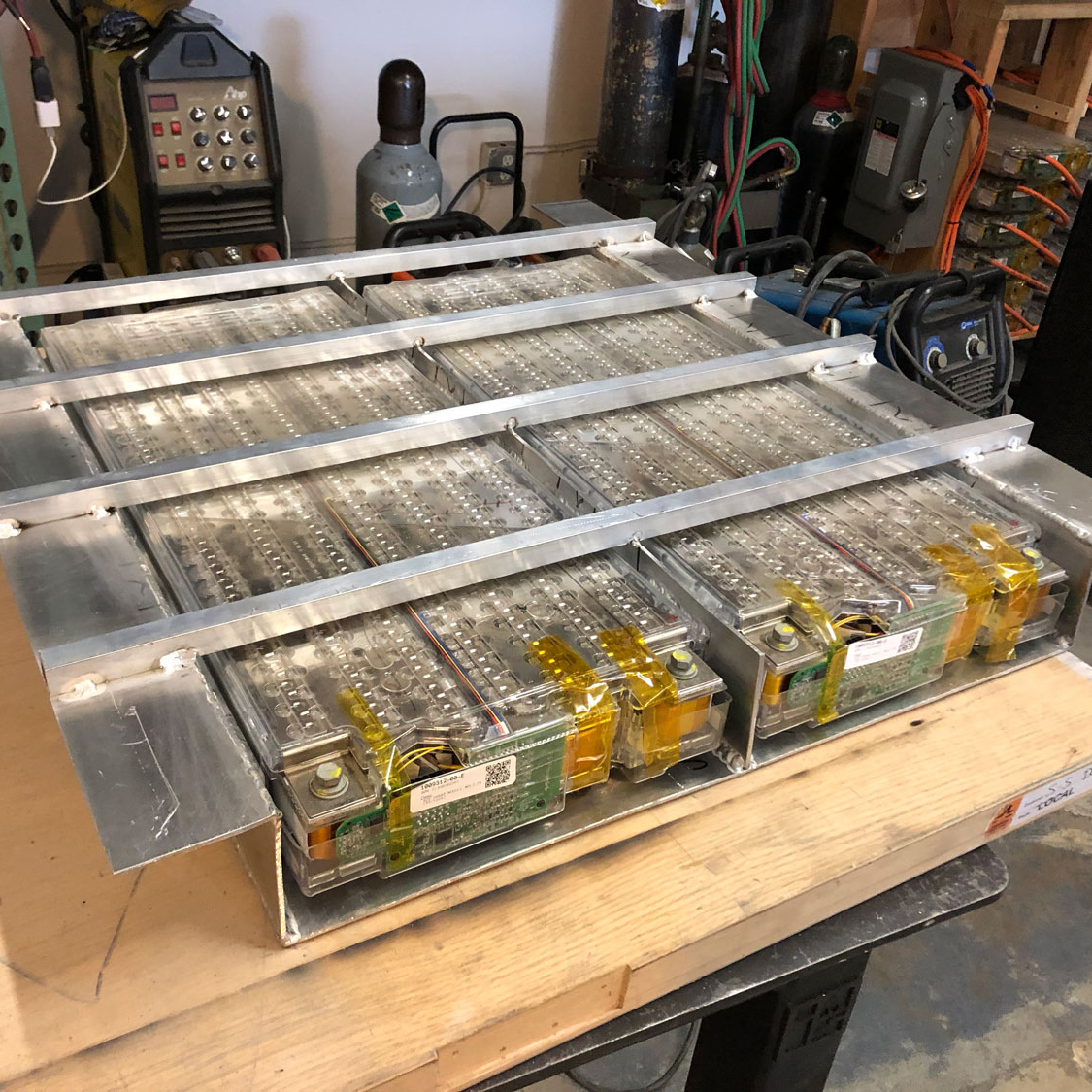

Here is our lower section complete with the modules slid into their tracks.

The full box is starting to take shape. We are able to get 9 modules across in the main body of the box.

Here you can see the 3 tiers of the box: 2 on the bottom, 9 across the center and 1 more on top.

Load it up with Modules

Once the box was complete we then loaded it up with our 12 modules. We used a combination of 2/0 copper wire and copper bus bars. The wiring chain begins and ends in a junction box that was built into the bottom, and accessible under the car.

Here’s an example of a custom bus bar which connects the two bottom modules in the chain. It looks rough now but will be plated and dipped in orange to look like the ones in the next photo.

This photo shows the 9 modules across looking nice with custom bus bars. Also the cable running to the top module and down to the junction box.

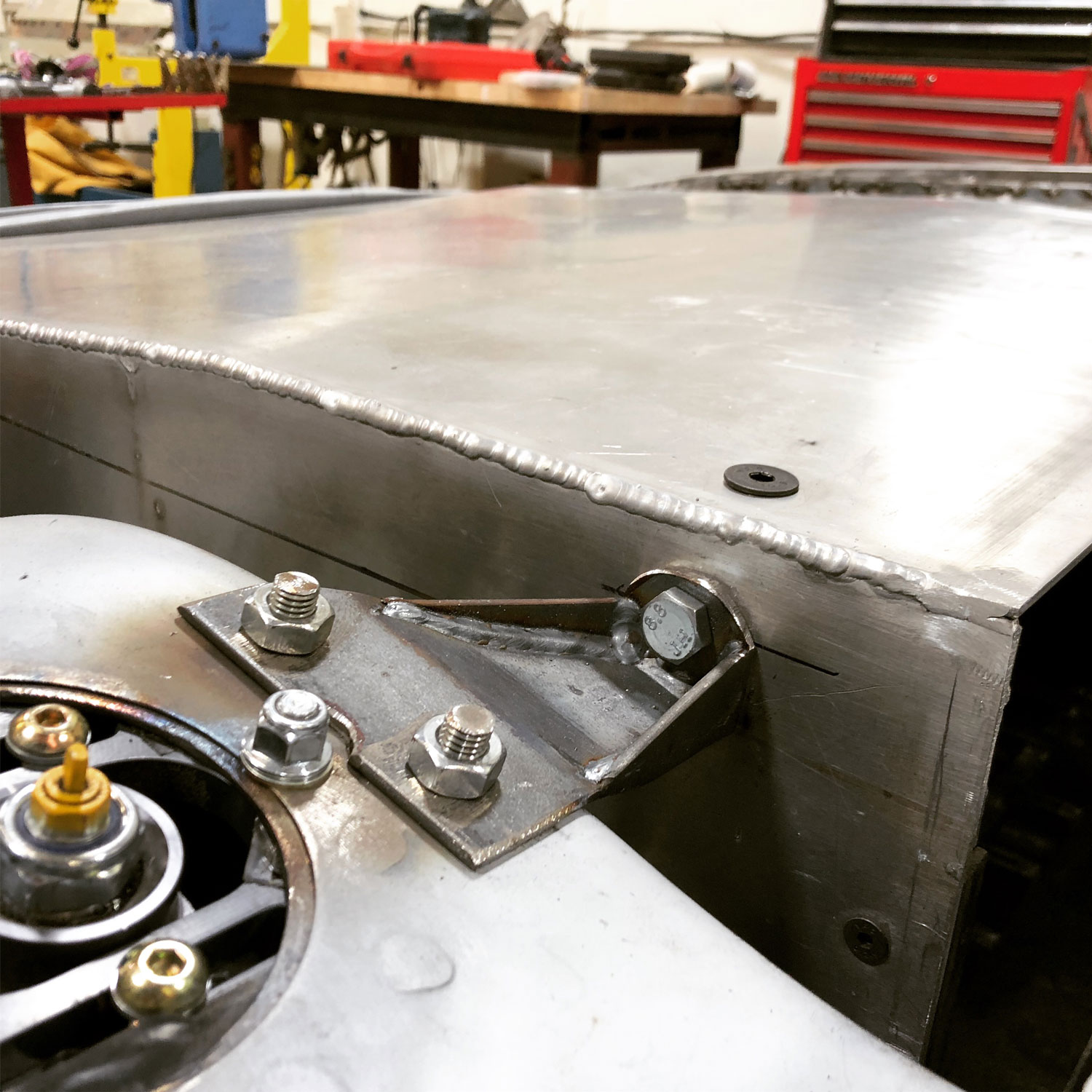

Each corner of the box has brackets to secure it to the car. The corners of the box are steel reinforced on the inside for this purpose and also for living the box.

Continued...

Battery Box

Unless we plan to drive our car using a very long extension cord, we have to get our battery modules off of their cart and into the car. Our plan is to get the majority of the modules in the engine bay, with a couple more in the trunk. Here’s the story…

Volts, Watts & Cells = Snoozefest, or Skip this Section if you Like

I have written and deleted here several times a fairly detailed explanation of how battery cells work. How you chain them together to increase voltage. How you group some of these chains together to increase their endurance. It was all very fascinating, but it took several pages and I fell asleep just editing it. So feel free to google all about it if you like.

My point in writing about it was to answer the question I often hear: “Why do you need so many batteries in your car?” It’s a terrific question. In fact, one of my favorite classic car EV conversions uses a high voltage Tesla motor like ours, but with Chevy Volt battery modules. Each module is not only smaller than the Tesla modules, they also output twice the voltage. We could get by with 6 smaller modules to properly run our car. That’s 1/3 of the size, weight, and cost of the Tesla modules. That sounds like a perfect solution.

Why then would we choose to go with 12 larger, heavier, more costly Tesla modules? kWh is why. Kilowatts Per Hour is the measurement of how long your module will last when being used. The majority of non-Testa EV battery modules have a very low kWh rating. This is finally beginning to change now that more auto manufacturers are taking EVs seriously, but we are years away from seeing these better modules in the used (salvage) market the way Tesla modules are today.

Teslas are good for 240 miles of range in some of their least capable configurations. Our car will be much lighter than a Tesla, but far less aerodynamic. We are confident that our 72 kWh battery configuration will get us over 200 miles of mixed city and highway driving. And in case you are wondering: no, we won’t be able to plug into a Tesla Supercharger on road trips to extend the range. However, we will be able to plug into the generic charging stations that are popping up everywhere.

Starting with an Open Engine Bay

We now can benefit from all the work we have done to open up that engine bay: The bulky steering box and linkage that we swapped out for our compact and low steering rack; The large brake setup which was swapped out and relocated into the transmission tunnel (thanks to Greg). We have earned ourselves a very wide open area for our new battery box.

A Sheet of Aluminum and a Table Saw

To properly mount and protect the battery modules inside the engine bay we need an enclosed box. To keep the weight down as much as possible, we built our battery box out of aluminum. By using all the space possible, our box will hold 12 Tesla modules. We will need to put 2 more modules into the trunk.

Aluminum cuts smooth and easy on a tablesaw as if it were a piece of thin plywood.

Tyler is a master with the tig welder. I learned a lot about welding aluminum on this project. Very tedious.

In between the car’s frame rails we are able to squeeze in a lower section holding two battery modules.

Here is our lower section complete with the modules slid into their tracks.

The full box is starting to take shape. We are able to get 9 modules across in the main body of the box.

Here you can see the 3 tiers of the box: 2 on the bottom, 9 across the center and 1 more on top.

Load it up with Modules

Once the box was complete we then loaded it up with our 12 modules. We used a combination of 2/0 copper wire and copper bus bars. The wiring chain begins and ends in a junction box that was built into the bottom, and accessible under the car.

Here’s an example of a custom bus bar which connects the two bottom modules in the chain. It looks rough now but will be plated and dipped in orange to look like the ones in the next photo.

This photo shows the 9 modules across looking nice with custom bus bars. Also the cable running to the top module and down to the junction box.

Each corner of the box has brackets to secure it to the car. The corners of the box are steel reinforced on the inside for this purpose and also for living the box.

Continued...

Last edited: